An Unhinged History of American Publishing, Episode 3.4: The Penguin Publishing Group, or: Waddling on the Tip of History's Iceberg

This isn't the story you think it is.

Properly told, the Penguin Books story might begin any number of ways. It’s just that no one tells it properly.

Instead, the stories go something like this: in 1934, a young publishing executive named Allen Lane visited his friend Agatha Christie at her summer house in Devon. At the end of a pleasant day, he waited on the platform at Exeter St. Davids for his train back to London.

At some point, Lane went to the station newsstand to buy a book. He came up empty-handed: the options on offer were all overpriced, hardcover dreck.

Ugh, Lane thought. Wouldn’t it be nice if I could buy a good book in some kind of cheap, portable format? Is that something anyone even sells? Anywhere?

And then it hit him: I could sell books like that.

Voila: Penguin Books was born.

Like I said: no one tells the story properly.

*

One might begin Penguin’s story more properly around sixty million years ago. In the Late Cretaceous period, penguins—the animal—rapidly evolved away from the common ancestor they shared with albatrosses and other marine birds.

This was just after the mass extinction that killed the dinosaurs. Our planet was a perilous, hot, rapidly-changing place, and to survive here, vulnerable species like seabirds had to find lots of new places to hide.

Among other adaptations, penguins evolved their signature tuxedo look around this time. It’s a particularly intense version of a camouflage adaptation thousands of other marine animals share: countershading.

Countershading is basically any animal color scheme involving a dark back and light belly. Say you’re a vulnerable animal in open water. If you’re all one color, even if it’s an ocean-adjacent color, the light reflecting off you is going to betray you to predators. You’ll look much brighter than the surrounding sea from above and much darker than the sea from below.

Countershading corrects for the betrayals of sunlight. It enables hiding in plain sight.

*

If the Late Cretaceous strikes you as too far back, another good place to begin Penguin’s story might be the Regency period—more specifically, London at the turn of the 19th century.

Let’s imagine we’re standing at the intersection of Vigo Street and Savile Row—the same block from which Allen Lane will one day launch his iconic book brand. You see that young man, impeccably dressed and groomed, on his way to visit the tailors’ shops? That’s Charles “Beau” Brummell, easily the most important menswear influencer in human history. The entire bon ton is following where he leads.

Seriously: he’s the most important menswear influencer in history. You’ve probably been influenced by him at some point. If you’ve ever worn a formal suit—menswear or just menswear-inspired—you definitely have.

When you think about it, this is bananas. Brummell died almost 200 years ago, and he was just some guy. He wasn’t a member of the aristocracy or even particularly rich, although he was well-connected. His dad had been the prime minister’s private secretary, which meant he got a place at Eton and ran with a powerful, aristocratic crowd in young adulthood—including the future King George IV, with whom he was exceptionally close.

Brummell had nowhere near as much money as the people he hung out with, though, and it showed. Especially on the sartorial front. At the end of the 18th century, after all, the look for hot young English aristo-bois was not so much “Brideshead Revisited” as “Andre Leon Talley At The 2011 Met Gala.” Think: capes, brocade, lace, silks, stockings, powdered wigs, buckles, jewels, and all manner of Francophone frou-frou. It all cost an astronomical amount of money.

Brummell had no hope of keeping up with these trends, so he just…changed them. He literally remade the entire enterprise of elite men’s fashion in his image. Imagine what would happen if Waldo of “Where’s Waldo” camouflaged himself by convincing every man in the Western world for the next two-plus centuries to wear his signature stripey hat and glasses, and you’ll have a sense of what a staggering thing Brummell accomplished. I mean. Really.

Clean lines, clean skin, clean hair, understated accessories, perfect fit, high-quality fabric: these were the hallmarks of an elegant man, Brummell said. Because he was BFF with the Prince of Wales—probably boning him, TBH—people listened. Of course elegant young Regency men didn’t bother with wigs or powder; they bathed daily, as Brummell did, so there was no need for artifice. Of course they eschewed snuff, booze, and rich food—not because they couldn’t afford it, mind you, but because they understood how gauche those things were. Most important, of course they wore sensible, plain, high-quality, military-inspired British suits, locally tailored and priced somewhere south of the stratosphere. This wasn’t France.

More than two centuries later, the tailors of Savile Row will still worship Beau Brummell as a kind of patron saint. So should we all, frankly, because who in the Tom Sawyer has ever been that good at convincing other people to ease his burdens?

To this day, thanks entirely to this one guy, men flock to Savile Row from literally everywhere on Earth to pay tens of thousands of dollars for their own bespoke version of what is colloquially known as “the penguin suit.”

*

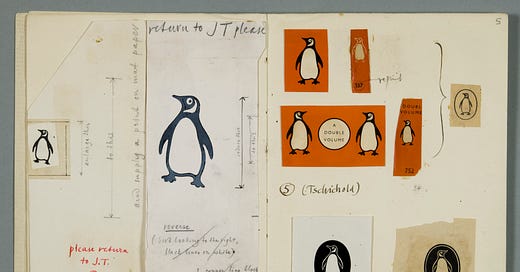

Sir Allen Lane wanted to name his new paperback brand after a bird. But which bird? He couldn’t decide.

His secretary at the Vigo Street office, a woman named Joan Coles, was the one who came up with it. In my mind’s eye, I see her looking out the office window and down Savile Row. I see her watching Beau Brummell’s sartorial descendants spill out of Henry Poole and the like, all dark tailcoats and and white shirts and Monopoly-man bellies.

I see the lightbulb going off in Joan Coles’ brain. What about a penguin?

*

In 2017, PRH even paid for a commemorative plaque to go up at Exeter St. Davids, site of Penguin’s conception. Two of Sir Allen Lane’s three daughters were there for the unveiling.

*

Allen Lane’s real last name was Williams.

*

Another good place to begin the Penguin Books origin story is in 1887. That’s when two bachelor-booksellers, John Lane and Charles Elkin Mathews, opened an antiquarian bookshop on Vigo Street, overlooking Savile Row. It was a brilliant location, given how many men with taste and cash already traveled to that block from all over the world.

Lane and Mathews named their bookshop The Bodley Head, hanging a bust of iconic 17th century librarian Thomas Bodley over the door. As this little act of drollery suggests, they were both pretty far up their own asses, albeit with excellent taste. The books they sold were aesthetic objets first, content second.

After seven years, The Bodley Head started publishing as well as selling books. This was all Lane’s idea; Mathews didn’t like the scope creep and eventually left the company altogether.

Lane, on the other hand, was delighted to publish books. He was friendly with many luminaries in Britain’s nascent Aesthetic movement and introduced their edgy, homoerotic Art Nouveau content to a scandalized but eager 1890s public.

The Bodley Head was particularly notorious as publisher of The Yellow Book, a scandalous literary quarterly art-directed by Aubrey Beardsley. If you’re familiar with Beardsley’s decadent work, you might be surprised to learn that he, like Beau Brummell, was not to the manor born. He was in fact a lower middle-class insurance clerk from Brighton—one who’d simply had the good fortune to meet Oscar Wilde’s ex, art critic Robert Ross, in his after-hours rounds as an amateur artist. An impressed Ross introduced Beardsley to Wilde and other Aesthetic luminaries, and the rest of his time on Earth is history: The Yellow Book; Salome; a very Bohemian death from tuberculosis, age just 25.

Aubrey Beardsley loved to shock and titillate. He loved inserting hidden sexual motifs into seemingly innocent drawings, like an x-rated Where’s Waldo. He got around the censors that way—to say nothing of his editors, including John Lane.

In sum, he loved hiding in plain sight.

*

Aubrey Beardsley also almost certainly used to fuck his sister. True story! The sister’s name was Mabel. This has nothing to do with anything else in this newsletter, but I felt compelled to share this fact with you. Aubrey Beardsley: sister fucker.

*

John Lane died in 1925 at age 70. In his mid-forties, he’d eventually gotten married—to an artsy widow—but the union had produced no children. In their absence, he left The Bodley Head to his sister Camilla Williams’s three sons.

His nephews were named Huey, Duey, and Louie. Just kidding: They were John, Richard, and Allen Lane Williams, and like Aubrey Beardsley, they were all lower-middle class boys from Bristol. Beardsley and they had even gone to the same random high school.

Unlike their fellow Bristol Grammar School alum, however, the Williams brothers contained little in the way of hidden depth. Or curiosity. Or, well, identity. In recognition of being made their uncle’s heir, the three brothers and their parents all changed their surnames (back) to his. Just like that.

I’m not sure if this was a legal necessity or just hardcore flattery for Uncle Moneybags. Either way, I think the end goal was the same: camouflage. The donning of an ill-fitting, glamorous costume.

*

Allen Lane admitted in some interviews that he actually hated reading. Books bored him. He also had no patience for scientists, preferring astrologers, who told him what he wanted to hear.

*

If one insists on beginning the Legend of Penguin Books in the 20th century, then 1932 is where you ought to do it. This was fully two years before Allen Lane’s eureka moment on the train platform, but it’s really the latest place a person who doesn’t have a personality disorder can begin. Thsi was the year John Holroyd-Reece, Kurt Enoch, and Max Wegner founded The Albatross Press, the European book publisher from whom Allen Lane stole everything.

Albatross published high-quality, low-cost paperbacks by authors like James Joyce, Aldous Huxley, and D.H. Lawrence. Within a year of launch, their books were explosively popular across Europe—particularly in Germany, where Weimar Republican elites tended to be fluent in English and fascinated by Anglo-American modernism.

Of course, though, these people wouldn’t be Weimar Republican elites for long.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to How to Glow in the Dark to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.