Some poetry that doubles as book publishing advice

Read the poems or just the TL DR here, which is "have mercy."

Here are some tips on writing craft that I found nestled in three of my favorite poems. I’m making this post free, so nobody can say I’m directly profiting off of it, and therefore it’s Fair Use: Analysis, and therefore PLEASE DON’T KILL ME, PROFESSOR GREENLAW AND MISTER ESTATE OF ALLEN GINSBERG.

[ahem]

Great writing treats all comers with love and mercy—including the author.

Check out this poem by Lavinia Greenlaw:

If you had asked me in grad school or even, like, four years ago, I’d have told you this was a poem about ~*~impossible love~*~: a perpetual orbiting borne of longing, circumstance, and goddamn it, WHY CAN’T MARIANNE AND CONNELL STOP PLAYING AND JUST ADMIT THEY’RE SOULMATES.

For whatever reason—getting older, the cynicism of the era—I now see that I missed the deeper meaning of this poem for almost a decade. Greenlaw’s primary concern here is framing, the little edges we all put around life’s incomprehensibility to make it survivable.

I see a speaker more interested in “the idea of those stars” than in the stars per se. I see her more interested in longing for this “you”—longing! A way to feel all the excitement of love while avoiding the clammy paws of intimacy—than in asking that person “what the fuck are you doing with this finger/scalpel business.” I see all of the “you” figures of my own youth, remembering how I myself envisioned them as star-crossed lovers. In fact, they were all 1. in the closet or 2. even less interested in actual intimacy than I was at the time.

A signature quality of brilliant writing is that its meaning matures and expands alongside you. It offers a worthy view on life’s incomprehensible continuum whether you’re looking through the steerage porthole of your youth or the sweeping verandah of your prime. Said window is somehow magically always just as big as your heart can bear.

The Age of Innocence is a work like this. So are the good episodes of The Simpsons.

How do you get this quality in your own writing? The answer is there in Greenlaw’s poem, too. You do it with love: mature, real, intimate love, the kind of observant and accepting love that Greenlaw the author has, but Greenlaw’s speaker is too afraid to develop yet. Real love is, as they say, patient and kind. It is observant and accepting. There is room in real love for all your mess and mistakes—your beloved’s, sure, but even more important, your own.

I think I missed the deeper meaning of Greenlaw’s poem for so long because of how much she loves and forgives the speaker. The speaker’s metaphor is intelligent, if a little melodramatic. Greenlaw doesn’t come out for a Director’s Commentary and assure us that yes, this poem is about a younger version of her, but guess what, she’s really evolved now, so yes, she knows the speaker is slapping a frame of ~*~impossible love story~*~ down on top of one that is confusing, embarrassing, and disappointing.

If Greenlaw cares at all whether we think she’s clever, she doesn’t show it. Rather, she lets 23-33-year-old Anna marvel through her porthole at the gorgeous, impossible love story she’s ready to see.

The universe contains infinite beautiful meanings. We don’t create this beauty; we just build the windows. So don’t distract your reader with your own insecurities. (“Well, you’re just in steerage now! Wait till you get to the VERANDAH!”) Let her marvel solo at the stars.

Good writing is always—on some level—absurd.

This is really just a continuation of the point I just made: good writing is merciful. Humor and absurdity are the best kind of mercy, because they contain only fellowship and no condescension. They make readers feel comfortable, grounded, and on an equal footing with you.

See this iconic poem from Allen Ginsberg:

You know how Emily Dickinson said, “tell all the truth but tell it slant / Success in Circuit lies?” I think she phrased it that way because the more precise version is not just less iambic but a whole lot less flattering for everyone.

Ginsberg’s poem is the HBO sitcom version of this point. The issue isn’t so much that the truth is unutterably dazzling as that humans are by nature schlubby, weak, avoidant cretins who hate to see it. Our appetites embarrass us. We satisfy them onanistically by night, avoiding the other hungry ghosts in the late-night supermarket as we shovel pints of raw need into our shopping cart. We imagine ghosts and fables into being so that our fears seem a little heftier, a little more reasonable, in context.

For most of us, the prospect of self-recognition, self-inventory, and self-forgiveness is so unbearable that the mere contemplation of it creates an out-of-body experience. WE ARE OUR OWN GROCERY-BOY OGLING WALT WHITMAN GHOSTS, PEOPLE. Ugh.

For me—and for Allen Ginsberg’s speaker, who, come on, it’s Allen Ginsberg—the only way I can approach this kind of huge psychological work is in a kind of parallel-play scenario. One in which I can sort of casually observe and learn from someone in the process, like Whitman and Ginsberg at the supermarket. One where no one’s watching or, like, taking pains not to watch me. Where I can deal with all of my shame, but deal with it slant.

And here I witness Allen Ginsberg in the same process. He is my lonely old courage teacher as he goes through his own parallel play process in the supermarket, his unmatchable literary superiors on one side and happy, paired-off, heteronormative 1950s families on the other. Together in one way and also not together at all, he and I can delight in squeezing the peaches of absurdity, letting the the pain of our self-understanding and the grief of our loneliness unfurl in the penumbras.

We’re going to repeat point number one here: good writing is merciful TO YOU, ITS AUTHOR.

I was a bit of a dick (har dee har har) to Emily Dickinson back there. That “tell all the truth” poem is a gorgeous metaphor about electricity! And she was presumably writing this when electricity was quite new!

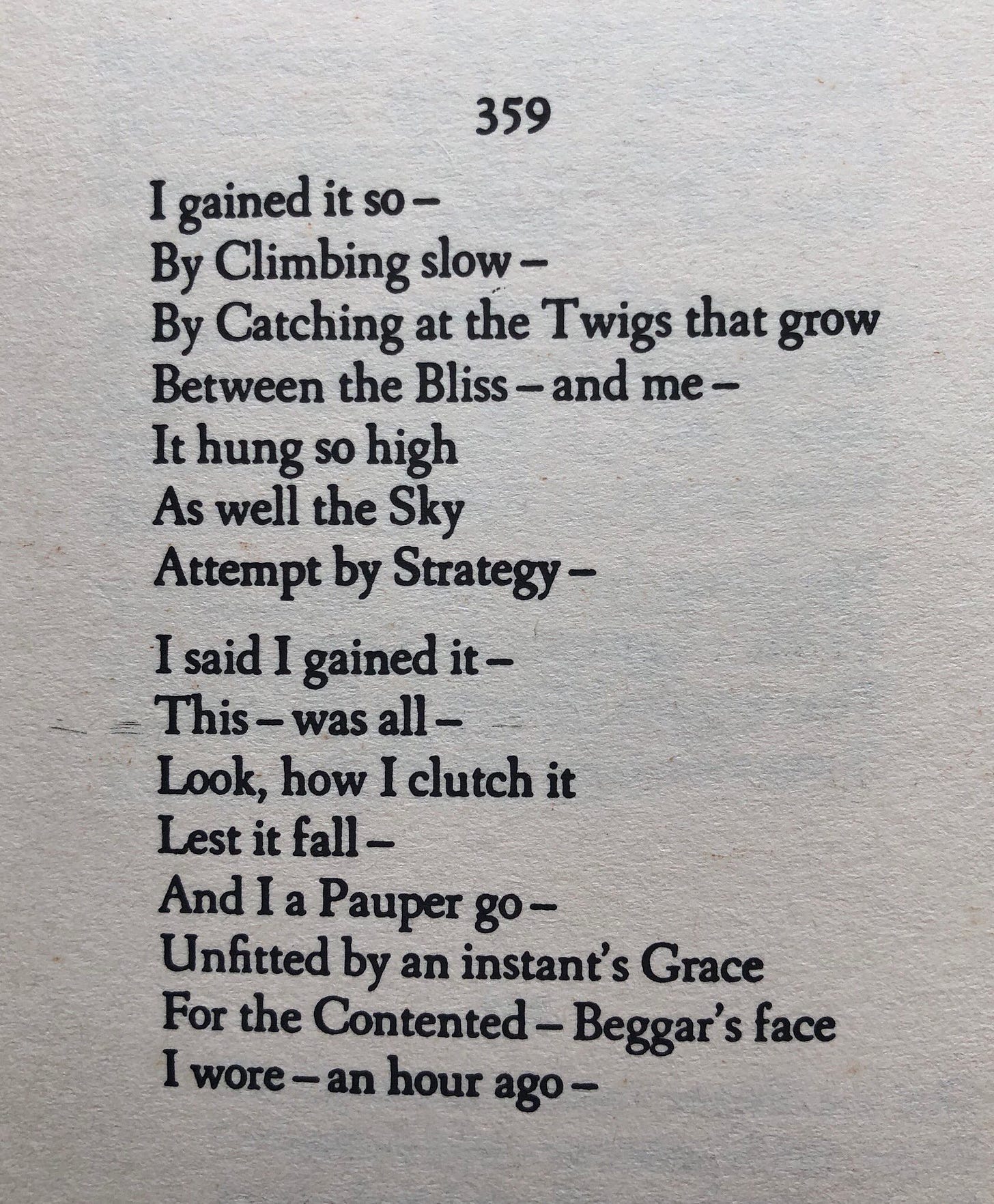

Let me give her a little more of my unexasperated focus here:

OH FOR GOD’S SAKE EMILY I AM TRYING HERE. I AM TRYING SO HARD. BUT YOU CAN BE SO ANNOYING SOMETIMES.

What Dickinson is describing is many authors’ fundamental relationship to their own goals and success. It is—look, it’s a choice. By all means, worry that you’re inviting the evil eye by reveling in hard-won accomplishment. Choose to stay committed to your belief in arrival fallacy, so that when your bliss in a hard-won achievement proves transient, AS ALL BLISS OF ANY KIND DOES, FYI, you have a nice, big zit of self-loathing confirmation bias waiting to pop. Plenty of the iconic authors I studied in college made this choice, including Emily D. herself.

Just please don’t call this “Grace,” you absolute Dickinson. It’s low self-esteem, nothing more, and if it doesn’t always hurt your career, it certainly never helps.

If there is a God going around the world dispensing Instant Grace, I’m pretty sure it’s not with the end goal of making writers feel stupid for making their dreams come true. That sounds like the kind of thinking that makes one of the greatest poets of all time spend her life COWERING IN HER HOUSE IN SOCIAL ANXIETY AND SHAME, PUBLISHING BARELY ANYTHING UNTIL SHE WAS DEAD AND SOMEONE ELSE PUBLISHED THE REST FOR HER.

Have mercy. Have mercy. Have mercy on everyone, especially you. The strength of your writing depends on it, and so does the sustainability of your career.