What Mike Knew

A post on intuition and meaning that is also about Mike Rose, my client who died last week.

Five days ago, just hours before what was probably going to be the last of our four editor meetings, my beloved client Mike Rose dropped dead. He woke up at dawn, sent me a quick email, walked into his kitchen, and—bam, there went the cartoon anvil of fate. Spontaneous cerebral hemorrhage. He was 77.

Mike didn’t die right away. Or maybe he did? Depends on how you define it. When the cops broke down Mike’s door Friday morning, twenty-four-plus hours after he went down, he was still breathing, but most of him had already left. In the bloodbath of his brain, only the brainstem remained functional. It kept chugging away, obliging, with the breathing and the circulating, until Sunday night.

In any case, Mike is 100% dead now.

Why am I telling you all this up front? Blowing my narrative wad? Because I’m a literary agent, dumbo. My job is to alleviate tension, not manipulate it.

Indeed, alleviating other people’s tension is something I have felt compelled to do for as long as I can remember. It’s why I write this newsletter; it’s why I was drawn to becoming an agent in the first place. I hate the sensation of knowing important information other people do not.

*

In literature, when we know important information that others do not, we call that “dramatic irony.”

Unsurprisingly, I HATE dramatic irony. All of it. As a developmental editor, I hate the lazy kind: those lame-o observations characters make when the author wants to end-run the hard work of world building. You know what I’m talking about: the family novel set in 1953 in which the family doctor blurts, “golly gee, I wish there were a cure for polio. But THAT’S never going to happen.” Groan.

As a human being, I also hate the skillful, subtle kind of dramatic irony. Yes, I know it is what powers most of literature. It’s what makes everything from Shakespeare to Shakespeare in Love so gripping. Audiences can’t look away until the characters find out the crucial information we know they’re missing. We watch, riveted, as our heroes twist in the wind of their ignorance.

Some people like this feeling. I, a spoiler queen, detest it.

Dramatic irony feels seedy to me—tawdry, oleaginous, and more than a little cruel, like one of those old-timey animal-abusing circuses. If there’s any magic to it, it’s the magic of con artists. The ring master manipulates people into feeling like they’re special, like co-conspirators, in the know. That is a powerful feeling. But it’s also a lie.

Not to mention that whatever “entertainment” we get from dramatic irony is not so much pleasure as schadenfreude. Pain and death are not absent in this seedy circus; they’re just happening to something or someone else. Someone or something who is also more helpless and ignorant than we are.

We enjoy watching this because it makes us feel, what? A little more powerful? Wise? In control? Like life’s horrors are all just slapstick and therefore bearable? Like we can’t get hurt as long as we stay inside the circus, because nothing inside this stupid tent truly matters?

*

Dramatic irony: Thursday afternoon, before I even suspected Mike was dead, I drafted a newsletter post. In it, I mentioned—for the second or third time—the thing I find most comforting about my job: At least when I make a mistake, nobody dies!

I sent it out Friday morning. Minutes after that, I called the cops in Santa Monica, asking them if they could please check on a missing client.

*

Dramatic irony: I knew something was wrong the instant Mike missed our Thursday afternoon editorial call. He was the most neurotic man I have ever met. He would never ever ever.

For some reason, though, I didn’t take the thought seriously. I told myself he probably just got confused by technical difficulties. That he was out of pocket. That he’d call later.

“Or maybe he’s DEAD!” The idea floated around like a diaphanous scarf, something designed for a witchy Instagram aesthetic and little else. I ran its weightless silk through my fingers. I emailed it to him, as a tease. “I’m beginning to worry you’re dead!”

When I woke up Friday morning, the scarf was strangling me.

*

Dramatic irony: During the year and a half Mike and I worked on his book proposal together, he drove me bananas. He was sweet and tender as they come, but also fussy, needy, and brimming with random neuroses.

Timing was the biggest concern. He had a vague sense that the clock was running out on his chances with this book, though he could never quite pin down why. He wanted it published immediately; he also couldn’t bear to let it go.

This made the editorial process excruciating. Month after month, we’d spend hours on the phone, puzzling out new structures and takeaways together, laughing often and occasionally veering off into long, intense philosophical discussions. We took each other so seriously. It was delightful. Then the next day he’d send me a long email talking himself out of having to do any of those edits at all. We’d scream back and forth at each other over email, make up, and begin the cycle anew.

Mike already had a full manuscript ready to go when he signed with me. He didn’t understand why we couldn’t just send it out immediately. (Because you already did that with your last agent, remember? And nobody bid. You signed with me specifically to change the book around so that it actually SELLS this time. Ps: what we need is a goddamn proposal, not a full manuscript.)

He wanted to know why my editorial feedback took longer and longer with every successive round. (Because our cycle of endless overthinking, followed by you changing nothing and then us arguing and writing long emails about our hurt feelings, is SO EXHAUSTING, MIKE. It feels wonderful to build such a strong connection with another human being, but WE LIVE IN A SOCIETY, AND THIS IS A PLACE OF BUSINESS.)

He wanted to know why seemingly no one, including me, understood the value of the Jack MacFarland throughline. (Because you have already published so much about your saintly high school teacher Mr. MacFarland and his transformative effect on you. We get it. You love him. He saved your life. But we’ve heard clear and consistent feedback from editors that this proposal needs less memoir and more takeaways.)

“But Mr. MacFarland is still alive!” he’d wail. “Don’t you see how miraculous it is that he’s still alive? I’m so worried he’ll die before we manage to sell this!”

I don’t know Mr. MacFarland. I’m sure he’s just super. I hate him anyway. What is he now, 8 bajillion years old? And Mike is the one who is dead.

*

Dramatic irony: Here is the last piece Mike published during his lifetime. It is a tender, quiet, devastating personal essay about growing up in South Central Los Angeles. He describes a childhood at once desperately lonely and overcrowded to the point of suffocation.

To survive, he’d sit at the desk in the one-room apartment he shared with his parents and zone out into elaborate mental flights of fancy. The best way to escape the darkness, he said, was to pretend it wasn’t there at all.

*

A few weeks ago, alarmed by Mike’s ongoing references to a minor recent outpatient procedure that had gone a little wrong and might or might not require follow-up surgery, I asked him: Should I be worried that you’re dying? Is there someone there to take care of you? Like a spouse? Or a child? Or something?

Never once in a year and a half had he mentioned anything about having any intimate relationships at all.

“Oh, thank you,” he wrote back. “I am blessed with more friends than you can imagine. I live alone, and my girlfriend is in Texas. She was going to zoom out here if I had to go into surgery, but I don’t.”

Over and over, he assured me that these medical issues, such as they were, were really nothing at all. He was doing great! He was doing so, so great.

And, I mean, he had no rational reason to believe he wasn’t doing great, at least according to what he shared with me. He eventually told me what the minor outpatient procedure had been, and I promise: you can’t draw a straight line from it to his brain exploding.

And yet.

*

Dramatic irony: Mike never married, or at least I don’t think he did. I know he had no kids. After the childhood he had, he seemed to like having a lot of personal space. Close to everyone, close to no one. Beloved by millions, died alone. Escaped the pain; didn’t escape it at all.

*

I loved Mike Rose so, so much, even though he also might have been the single most aggravating client I’ve ever had. There was no way in hell any commission I’d ever receive on his book would financially justify the time demands of our relationship, let alone the exhaustion.

I stayed in the relationship anyway. Happily. It brought me so much joy.

Never in the depths of orgiastic moroseness could Charles Schulz have imagined a neurotic ruminator more determined to wrest disappointment from his every success than Mike Rose. Neither for all the wonder in Schulz’s childlike soul could he have dreamed up a character more warm, tender, careful, open-minded, sincere, brilliant, tenacious, and faithful.

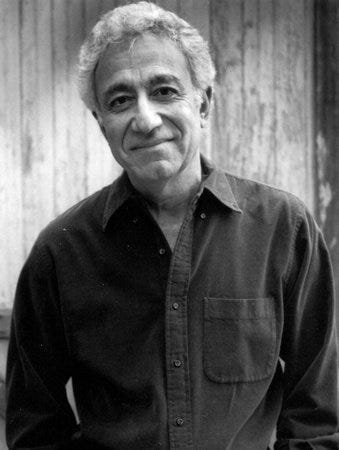

Mike Rose was like Charlie Brown, but not a blockhead. And unlike Charlie Brown—can I say this? I mean, he’s dead!—he was kinda hot. One of those dark-horse septuagenarian hotties (a salt and pepper horse?) whose hotness just kind of sneaks up on you over the course of several months. He struck me as 99% unaware he was hot and 1% absolutely aware.

Oh, and I haven’t even told you about his career. He was an icon in education scholarship, one of the most respected thought leaders and mentors in the history of the field. He was a mentor to thousands of adoring teachers and students and taught in schools for many years himself.

By the time Mike and I started working together, he had already published not one, not two, but eleven groundbreaking commercial books. His biggest hit, Lives on the Boundary, still sells a ludicrous number of copies every year, 32 years after its initial publication.

He told me the book we were selling together, When the Light Goes On, was the most dear and precious thing he’d ever written, the capstone of his life. To his melodramatic outrage, his longtime literary agent had reacted to it with a “meh,” and yadda yadda, their professional relationship of 25 years ended.

Eventually, he saw Neon’s branding and my bio and thought: this woman looks adequately deranged for my needs. In particular, he loved our corporate motto, “time for a new story.” Which he told me many times. SO many. Especially during our arguments.

I can’t get editors to buy this book if you don’t add some more takeaways here, Mike, I’d say.

But you’re different!, he’d reply. You know what those editors don’t! That it’s Time For a New Story!

Yes, I’d say, but the point of that is that intelligent and adaptable new stories help us to navigate the challenges of reality. For instance, it is a challenge that you want a traditional book deal from a big publisher for a passion project. We’re not trying to magic these challenges away altogether or pretend they don’t exist. We’re trying to NAVIGATE THEM.

*

The point of When the Light Goes On is simple: education is about people, not concepts. In the past 50 years, Americans have acted as though the opposite were true, hyperfocusing on one technique or metric or tech device after another. We’ve focused on students’ performance in just one narrow band of the many intelligences people have—cognitive, embodied, emotional.

In short, we’ve dissected students into parts instead of making room for the whole. And Mike, ever a fan of personal space, found that reprehensible.

In the book, Mike interviews more than 200 people from all walks of life—class, race, age, gender, sexual orientation—to isolate the moment they fell in love with learning. The moment that hope and curiosity replaced depression, disengagement, and despair. The throughline of their stories is this: I learned to take myself seriously the moment someone who cared about me started paying attention.

Were Mike alive, he would be wailing, “it’s more complicated than that, Anna!” But ha ha, Mike, you’re dead. There’s no one left to stop me from me reducing down all the pitchy, flavorful takeaways I want.

*

The last email Mike sent me was characteristically neurotic. He asked if we could talk later that day about the remaining players on our sub list—the ones who hadn’t responded yet. I knew why he wanted to do this, and it made me groan out loud.

There was one editor in particular, a woman for whom he’d blurbed another author’s book, whose nonresponse agitated him terribly. Even though we had four great editors pursuing. Even though this other editor worked at a company with a microscopic budget, so she probably wouldn’t even be able to compete with the demonstrably enthusiastic people. And even though I had told him THREE TIMES that this woman’s out of office SAID SHE WAS ON VACATION.

I eventually realized that Mike didn’t care about whether this editor would acquire When the Light Goes On. Not per se. He was just scared she’d forgotten about him. That he didn’t have a place in her regard anymore. That he had thrown a rope out to a colleague whose esteem he cherished, and she’d let it drop.

I was so annoyed. NOT THIS EMO SHIT AGAIN. So even though I saw the email arrive in real time, I didn’t answer. I told myself, I’ll talk about this on the phone with him later.

Dramatic irony: it was the last communication of any kind he ever sent anyone. And I didn’t catch the rope.

*

The point of all this, in case it’s understandably lost on you, is that Mike Rose was right. It was time for a new story, for him and for me. We were setting off together (and separately; life is always both) on a journey unlike any other.

Mike just didn’t know what new story he was in yet. And neither did I.

Our intuition pulled both of us forward into that new story, even though our eyes couldn’t see it and our minds couldn’t conceive it. Because of course, consciousness and the senses exist to help us avoid pain. And since they’re focused on doing that full time, they’re never going to get the story exactly right. Such is the embarrassment of being human.

Our hearts know what’s up, though. And the stories we tell ourselves to justify our feelings aren’t what matter, in any case. As Mike knew in his bones, our presence with each other is what makes the light go on, what makes a human life worth living. Just being there for each other, paying attention and listening to our people in the fullness of their humanity.

That’s what you taught me, Mike. I love you so. And I will carry you in my heart forever.

[NB: I went back into the text of this essay on July 20, 2022 to edit a couple of minor factual errors I’ve realized I made in the year since I initially published this piece. The biggest one was my misunderstanding that the editor Mike emailed me about just before his stroke was one he had worked with on one of his own books. She wasn’t; she was someone for whom he had blurbed a book, and he still held her in high esteem.]