What people like me mean when we tell you that sad book you're working on "needs to be more uplifting"

This is one of the most common notes authors get from agents and editors. It sounds like toxic positivity--barf--but it's not; it's an imprecise way of phrasing a really important concept.

At some point, whether they’re writing novels or nonfiction, authors who truck in dark subjects—death, suffering, tragedy, illness, addiction—almost inevitably hear this note from a literary gatekeeper:

“Your book needs to be more uplifting.”

This is one of the most common pieces of feedback agents offer in one-on-one sessions at writers’ conferences. It’s also one of the more common justifications for rejection included in personalized rejection letters.

It’s certainly the editorial note that grosses the largest amount of authorial outrage by volume. It sounds so fucking offensive. How do you make a memoir about living with terminal cancer uplifting? How do you make a Holocaust history uplifting? If one were to write a book about what’s currently happening in Palestine, would one need to find a way to make that uplifting? Retch.

Like a neon “good vibes only” sign in a 2010s coworking space, this advice crackles with cheugy. Upon seeing it, many authors think, oh look, this is a place where assholes hang out. They think it’s a call to reduce, reframe, and ultimately dissociate from reality in the name of “being positive” while encouraging their readers to do the same.

Readers don’t want denial; that much is true. (Unless they’re anxious, emotionally immature cable news fans picking up reactionary political screeds, I suppose.)

Denial is like fentanyl: it only helps people in the most superficial way, and for a few minutes; after the first hit, one needs more and more of it to benefit at all; too much of it will suck all the meaning and purpose from one’s life and probably kill you.

When people buy dark books, they generally don’t want fentanyl. They want real help: information, recognition, catharsis, relief, guidance, and the deep sense of safety that comes from knowing other people willing to acknowledge that reality is real.

Sad Book Readers, in other words, are Dantes in search of a Vergil. They’re lost in the woods outside of Hell. The last thing they want in that moment is for Joel Osteen to pop out from under a rock and be like, “JUST STAY POSITIVE, GURL!”

Here’s the thing, though: most agents and editors who tell you to make your book “more uplifting” don’t mean it in the sense of “add some toxic positivity.”

I mean, I can’t speak for everyone. I suppose if you’re writing a prosperity-gospel inspirational cheer sesh for an evangelical publisher, your circumstances might be different. Ditto if you’re trying to prop up America’s MLM industry through Rachel Hollis-adjacent self help. The people who represent and publish those kind of books probably do want you to be less of a downer. But I’m not one of those peopole, and neither are most top agents or editors.

When people like me give out that note—“your book needs to be more uplifting”—what they’re generally doing is trying to convey a hugely important but complex editorial point in a succinct, memorable way. In the process, they’re losing some linguistic precision.

The Merriam-Webster definition of uplifting is “inspiring happiness, optimism, or hope.” When agents and editors tell authors to be “more uplifting,” the last of these is what they generally have in mind. The want authors to find the hope in their story, the crystalline vug glittering amidst the granite.

Even so modified, however, this note isn’t as precise as it could be. Terminal cancer is pretty hopeless, after all, yet When Breath Becomes Air was a massive hit. The Hiroshima bombing: also not known for being super hopeful, yet John Hersey’s account of it remains a classic.

So what exactly is the note?

The note is that authors are smart, agents and editors are dumb, you shouldn’t listen to agents and editors, and there is no one on Earth smarter than you, Bernice.

Just kidding. I’m sure you’re just brilliant, but most of us on this side of the table are, too. ::flips hair::

Unless your book exhibits the precise qualities editors are asking for when they give you this note—however much they’re struggling to find the right words—it simply won’t have a chance on commercial submission. It also probably won’t be a good book. It might be a satisfying-blog or TikTok series or obituary, but it’s never going to satisfy readers on the level they expect from literature.

So, yeah: you need to take the note. And if words like “uplifting” and “hopeful” leave you feeling confused and defensive, as is understandable, approach this note via one or more of the metaphors below.

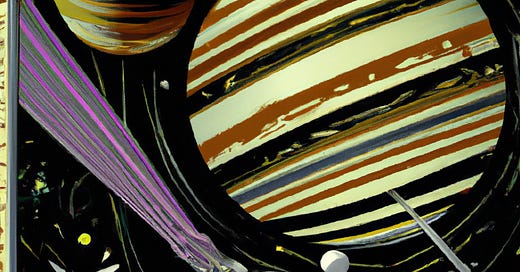

METAPHOR ONE: YOU ARE NASA, YOUR BOOK IS JUPITER, YOUR READER IS THE VOYAGER SPACECRAFT, AND IT’S YOUR JOB TO MAKE SURE YOUR READER LEAVES YOUR BOOK DOING WHAT THE VOYAGER SPACECRAFT DID AFTER ORBITING JUPITER

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to How to Glow in the Dark to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.