Your readers don't need your advice, quips, aphorisms, ego, or projections. They just need your presence on the page.

What one bonkers work lunch eight years ago taught me about the power of radical presence in a publishing career.

Here is something I can tell you for sure: never again in my career will I have so delightful or so bananas an editorial lunch as the one Maria Guarnaschelli treated me to in the summer of 2014. There is just no way.

For starters, there’s the problem that Maria, a legendary editor who spent the last two decades of her career at W.W. Norton, is no longer alive. Her retirement in 2017 and death in 2021 were a huge loss to American letters as well as all of us in publishing who live for a good chaotic aura.

Maria Guarnaschelli is not the main point of this week’s newsletter, but please allow me to tell you about her for a moment anyway.

An Italian-American refrigerator salesman’s daughter from Massachusetts, Maria also had a master’s degree in Russian literature from Yale and great, big, staring, existentially unsettling eyes. I’m pretty sure she was some kind of anthropomorphic owl queen in her spare time. She was prone to forceful nonsequiturs.

Famous for her editorial work in two categories—1. bestselling first-time popular nonfiction by academics and 2. cookbooks—Maria could go equally hard into intense monologues about both Mikhail Bakhtin and carbohydrates, and she did. Oh, SHE DID. But then, when she was done, she wanted to know what you thought about everything, too.

We met for lunch that day at an Italian place she liked. What happened next was pure dada. Maria, who was meeting me IRL for the first time and knew zero about my dietary preferences, announced I AM GOING TO ORDER FOR BOTH OF US. She then did so.

The dishes she ordered included olive oil-flavored savory gelato and all kinds of weird pasta, one of which I’m pretty sure contained squid ink? In any case, they were all perfect.

Every twenty minutes or so throughout the lunch, I had to get up to go milk myself in the bathroom. I was weaning my oldest baby that week, midway through one of my first big postpartum trips to NYC. Twenty-nine years old and frazzled AF, I was trying to stuff myself into my old work clothes and former identity and desperate to impress this industry legend across the table from me. Things were literally and figuratively leaking all over the place.

If Maria noticed how disheveled I was, she didn’t blink either one of her penetrating saucer eyes. Instead, we talked about psychoanalysis; my client Colin Dickey’s Ghostland, which she wanted to buy; the general concept of haunted places as a Freudian return of the repressed; and finally, if I recall correctly, some of her pasta-related gripes, the proper preparation of cacio e pepe being an object of significant consternation.

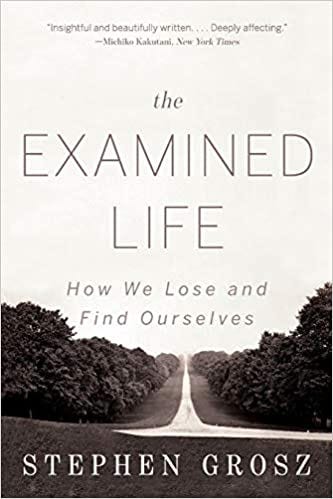

When we were done eating, she said I BROUGHT YOU THIS MARVELOUS BOOK I JUST PUBLISHED HERE IN THE STATES. Thence she whipped The Examined Life by Stephen Grosz out of her purse, sliding it across the table until it was under the agony boulders of my breasts.

IT’S BY AN ANALYST WHO CAN REALLY WRITE, she said. Then, having already paid for us both, she abruptly got up and left.

I never got the chance to work with Maria beyond that. I wish. But boy, did our lunch stick in my memory—and boy, has The Examined Life endured on my shelf as one of my all-time favorites.

I’m not sure how Maria knew I would love this book, just like I’m not sure how she knew I’d love savory gelato. But Maria Guarnaschelli was a shot caller, and with me, she called correctly.

If you haven’t read The Examined Life, you must. It’s short; it’s a beautifully-written meditation on human nature. And most important for our purposes in this newsletter:

Grosz’s book offers excellent insight about how people connect with each other through—or perhaps in spite of—language.

His essays encourage us to spot the differences between what people say they want and what they truly need.

Through him—his expertise, but also his mistakes—we learn how to pay attention to ourselves and others as we are, not as what we fantasize ourselves to be. Compassion and humble curiosity are the core skills of a great psychoanalyst; they are also the core skills of a great writer. And The Examined Life offers a master class in both.

Here’s just one example of the insight this book offers—wisdom I’m desperate that more of us would internalize, inside and out of our publishing careers:

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to How to Glow in the Dark to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.