The mark of a philistine, weak writer, and unimpressive coworker: if they can't recognize the value of a thing up front, they decide that that value must not exist

If you want to maximize your long-term prospects in book publishing and cultural memory, do the opposite.

If you’re serious about success in book publishing—especially in the long term—please remember the following advice:

BE A LEOPOLD, NOT A PINCHOT.

The wisdom here is self-evident, AMIRITE?

Just kidding. It’s not. Walk with me; I’ll explain.

How much do you know about Gifford Pinchot?

Unless you’ve studied environmental history—and weirdly enough, a large number of you who subscribe to this do! LOVE YOU—I’m guessing the answer is “not much.”

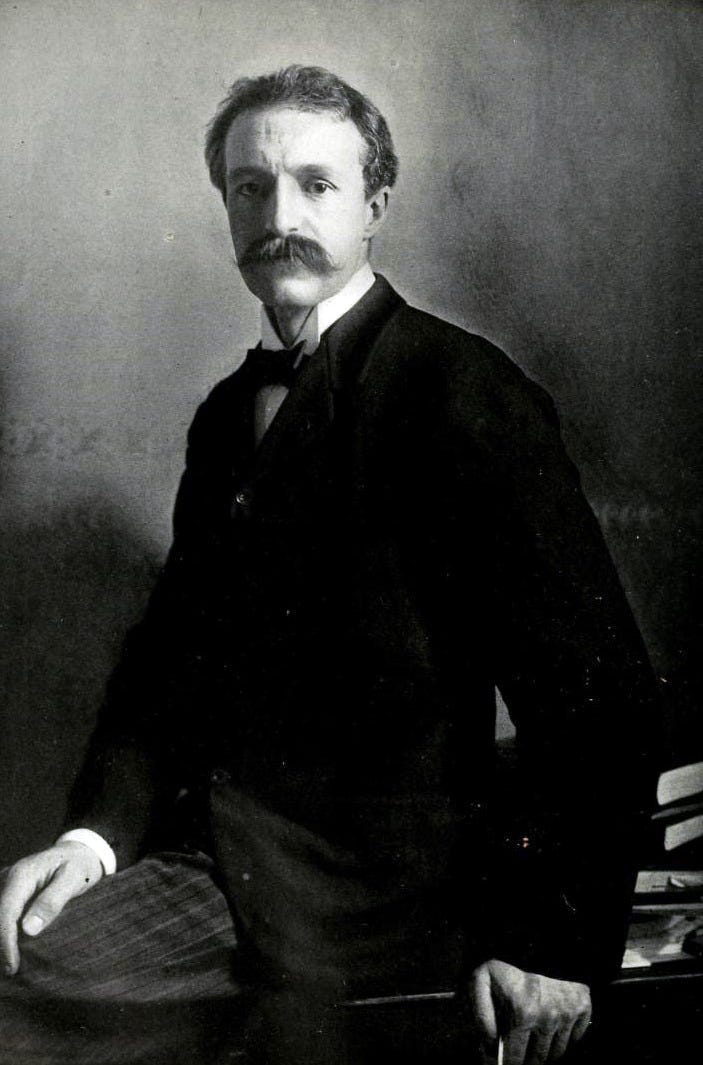

Here’s a picture of ol’ Gifford. He was the first leader of the US Forest Service, BFF of Teddy Roosevelt, and OG champion of progressive management, the philosophy still governing most US wildland management policy:

Pinchot was brilliant and tenacious. I think he meant well. His influence is everywhere you look in America’s national parks and forests; for fuck’s sake, he’s the reason they exist in the first place! He fought hard and at times dirty to snatch these places forever from the maw of Gilded Age industrialism. You’d have to be C. Montgomery Burns to object.

Yes, and: Pinchot’s legacy is….complicated. He contributed to and in some cases caused some real long-term problems in the American landscape. He did this in several ways, all of which fall into the general category of OH MY GOD, EVERYTHING IN AMERICA IS LITERALLY ON FIRE BECAUSE OF THIS GUY AND A FEW OTHER BOZOS’ BABY-MAN ATTEMPTS TO FILL THEIR UNMET PSYCHOEMOTIONAL NEEDS WHILE CALLING IT CIVIC DUTY.

First: Pinchot and the other progressive-management guys made the case for public lands by arguing that their worth lay in the known, measurable value they provided the American people. They argued that America needed a self-sufficient and sustainable long-term supply of wood, water, mineral ore, etc. to grow and maintain its strength, independence, and power. This need was so important as to necessitate government takeover and stewardship of such resources.

Second: Pinchot was Machiavellian in his quest to grow USFS, and some of the tall tales he told to secure Congressional funding 110+ years ago remain baked-in tenets of American land management policy.

Take, for example, preventing forest fires, a thing you can’t actually do. In 1910, the future looked especially shaky for USFS—and this was coincidentally a TERRIBLE year for forest fires, one in which lots of people died. The public was traumatized and desperate to Do Something. And wouldn’t you know, in came Pinchot, guns blazing, telling newspapers and Congress that if they only funded USFS, forest fires would become a thing of the past. All forest fires. Forever.

Pinchot was not a dumbdumb. He knew fires are a natural and necessary part of forest life; trying to prevent them only makes them more catastrophic, if also further apart (at least before climate change! Now they happen all the time).

If Smokey the Bear were honest, here’s what he’d be saying in his PSAs: “‘only you’ can’t prevent forest fires; fire management is the highest standard available, and such management must necessarily be collective, choreographed by communities in a cycle of controlled burns on a stage of carbon neutrality.” This is ATROCIOUS ad copy.

Third: Pinchot’s real motivations for doing all of the above appear to have been a little more pathetic than he let on. This is relatable, but still.

This guy ran the same psychoemotional scam that countless pastors, politicians, cult leaders, and bosses have run before and since: one in which a person who has never quite left the egocentric developmental phase tries to convince everyone around them that they’ve figured out how the world works—and wouldn’t you know, it works in a way they alone have the capacity to lead and interpret.

Sure, Pinchot and his friends promoted their vision in the rhetoric of high patriotism, deploying all the persuasive skills they’d honed with upper-crust New York tutors and Ivy League professors. But their true animating anxiety seems to have been self-preservation: that baser thing all of us humans feel in times of great social change. As all of us have done at one time or another, they were projecting their own annihilation fears onto America’s unsuspecting conifers.

Existential terror squirmed just beneath the surface of their stump speeches. Free public lands will give all Americans access to wholesome leisure! they argued. (Subtext: And maybe once the proles have these bread and circuses, they’ll forget their plans to rise up and kill us all.) They’ll bring poor and rich people together into Rugged Manly Fellowship within America’s scenic campgrounds! (And maybe once the proles have a chance to see we’re all nice guys who love fishing and shit just as much as they do, they’ll be cool about the centuries of exploitation and genocide.)

It’s not a coincidence that national parks and the forestry service were born simultaneously with the ascension of America’s organized labor movement. It’s also not coincidence that this was an era marked by mass immigration, racist legislation, hate crimes, and the resurgence of the KKK. Nationwide, marginalized populations were making marginal gains in power and size, and boy did that give America’s powerful white men a case of the uh-ohs.

Oh yeah — did I mention Pinchot was also a FLAMING EUGENICIST? ‘Cause he was! He served twice as a delegate to the International Eugenics Conference and for ten years on the American Eugenics Society’s advisory counsel. Meanwhile, Pinchot’s ally Madison Grant, founder of the movements to save both the American bison and California redwood, was a balls-out white supremacist whose published book of white supremacy apologetics—a book whose jacket featured A GLOWING BLURB FROM TEDDY ROOSEVELT—was later a hit with THE ACTUAL NAZIS.

Psst: I don’t know if you’ve heard, but hatred generally starts in a place of existential fear. No one is more dangerous to himself and others than a person recently bereaved—or facing some imminent loss—of power, status, and respect. This is the moment in a human life at which pretty much all of us become our most frightened, cruel, and foolish. Our blind spots expand and our capacity for insight contracts. It’s the emotional state in which people tend to make life-ruining mistakes. History-altering mistakes. Bad, bad, bad mistakes.

Of course, the above isn’t just true for old-timey foresters with a case of noblesse oblige. It’s also true for writers, readers, critics, agents, and editors. The past 15 years have been a time of nonstop existential tumult in this industry; the chaos has only increased as the years have gone on. Power is shifting. Resentments are rising. People are scared. Which is why—like America’s trees—America’s publishing professionals now face intermittent conflagration and widespread burnout.

It’s so tempting to react to all the trauma by pulling a Pinchot, attempting to force all of spacetime under the thermodynamic law of our own ego. We’re terrified that if we don’t succeed in such ego impositions—which, spoiler alert, we won’t—time and change will annihilate us; we’ll be erased. Which is actually true! What’s NOT true is that we can prevent this from happening.

Some day soon, the world will evolve beyond us. So will we. We will evolve beyond us. Which is cool! That’s the meaning of life.

I’ll come back to all that in a moment. In the mean time:

Does the name ”Aldo Leopold” mean anything to you?

I’m going to run though this guy’s deal in as quickly as I can. I don’t want to bore you with too much environmental history here, and I also don’t want to open my amateur ass up to even more factual errors than I’m sure I’ve already made. THE POINT HERE IS THE METAPHOR, NOT THE HISTORY, DENISE.

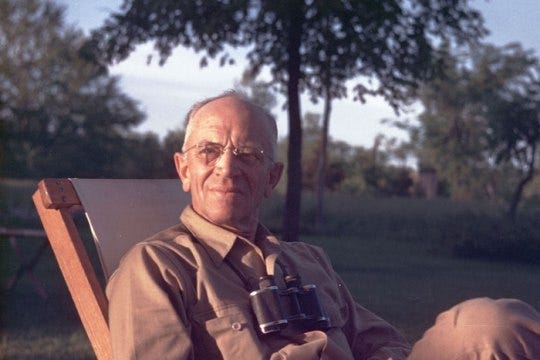

Aldo Leopold was a philosopher, naturalist, and professor at the University of Wisconsin. Together with people like Rachel Carson and E.O. Wilson, he’s now celebrated as a pioneer of un-anthropocentric environmentalism.

In A Sand County Almanac, his gentle whisper of a book, Leopold asked the public a revolutionary question:1 what if ecosystems contain complexity, meaning, intelligence, and value beyond our brain’s capacity to imagine? Like…all ecosystems? The ecosystem of a forest? The ecosystem of a human body? And what if we protected and held space for all these unknown unknowns…just because?

Leopold’s was a philosophy of wonder, trust, humility, and acceptance. It was one of “I don’t know everything, and I don’t need to.” In the past 50 years, environmentalists have deployed it to save bald eagles, close the hole in the ozone, and repair the food chain in Yellowstone National Park. Many such environmental calamities were caused by human arrogance, the destruction of things we presumed to be “useless.” They were saved by our humility.

But of course, in the end, all things die anyway.

*

You know what’s ironic? Aldo Leopold died of a heart attack at age 61—a heart attack he suffered while helping his neighbor fight a fire in his yard, one that might have otherwise spread to nearby forests. Only you can prevent forest fires, amirite?

Just kidding. Forest fires are going to happen to us no matter what we do. So will death.

Humanity likes to gas itself up with false assurances about our capacity to keep ourselves safe. We talk about ourselves as if we’re powerful enough to make or break the entire enterprise of forest fires. Or “ruin the planet.” Or “wipe out life on this planet.”

Ha ha, isn’t that cute? Like we stand a chance of wiping out fungi and extremophile bacteria. Please. They’ll be here for a long, long, long time after us.

No matter what we do or don’t do, the planet’s going to be fine. Life on this planet will continue evolving with or without us until the sun engulfs everything. As humans, our choice is more whether or not to remain in denial, acting the fool until such time as the planet ruins us.

What kind of a joke is this, being forced to experience consciousness as and powerlessness at the same time? To experience life as individual organisms on a planet where all of life’s meaning and power is collective and communitarian?

At least life has meaning, though. It has real, transparent, obvious meaning. Lots and lots of people have already pointed out what the meaning is, from Aldo Leopold and Robin Wall Kimmerer to Jesus, Buddha, and all the indigenous traditions of North America.

Most of us are still somehow confused, however, so just in case, I’ll repeat what all of them have already told us. The meaning of life is TO EVOLVE. It’s a verb. All of this ::gestures out the window::—all of us organisms—are part of one big ongoing organic exercise in exploration and expansion. To what end? Who the fuck knows! I don’t think there is one! The meaning is the generative action itself, the constant expansion of possibility.

This means the following things are also true:

*if the meaning of life is to evolve, that means it’s born between individuals, not within them. Therefore, people who try to locate the meaning of life entirely within themselves and their extant strengths live less meaningful lives than people who do the opposite.

*The meaning of life isn’t annihilated by death, failure, dead ends, freak accidents, or entropy. It’s powered by them.

*To the extent that we have any say in the depth and meaning of our own life, it’s a function of how well and deeply we love the other life forms surrounding us. I’m not just referring to human beings in a cutesy way here, incidentally. I’m saying all the other life forms.