"We are attempting to survive our time so we may live into yours"

Or: the most beautiful writing advice ever to drift through interstellar space.

Jimmy Carter’s funeral is about to start at the National Cathedral. I’m coincidentally nearby, sitting in my car and somehow crying yet again about the letter he wrote for the Voyager space probes back in 1977. (It’s 2025, baby. No subject is too esoteric for weeping.)

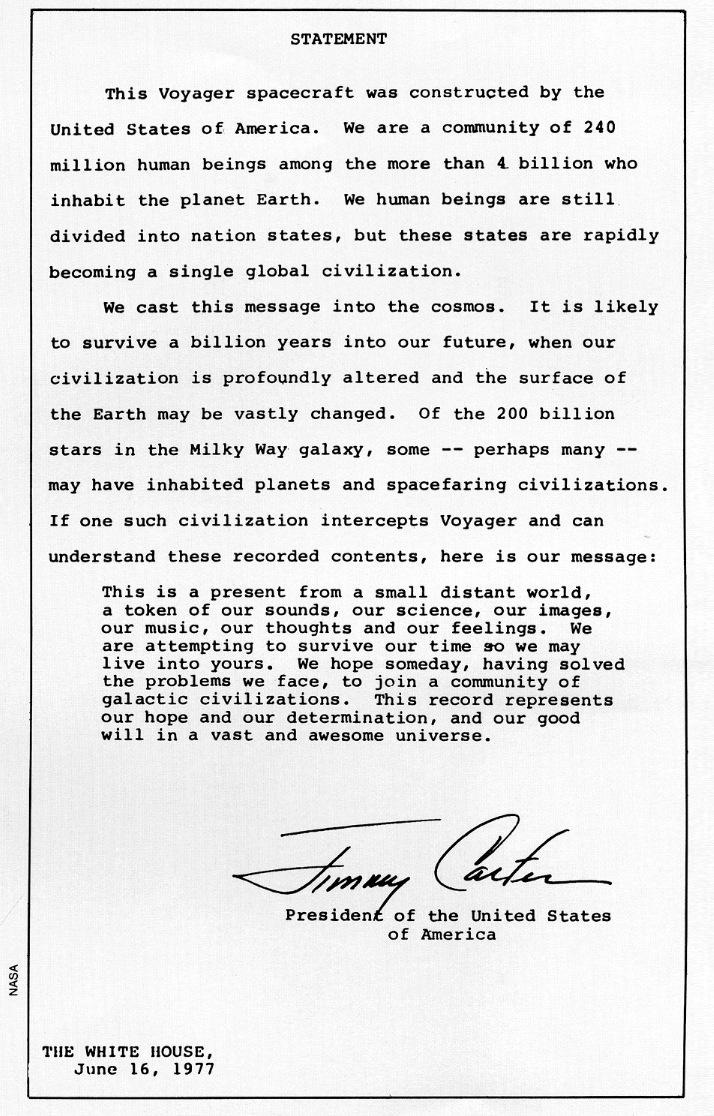

This letter—attached to the golden records on Voyager 1 and 2, addressed at least ostensibly to extraterrestrials—is perhaps the most underrated presidential communication in history. It coruscates with poetry in every paragraph.

It also contains a line I wish all of you would hang on your walls. It’s such an important reminder of why we’re all here—in book publishing for sure, but also more generally on this planet.

See if you can spot the one I’m talking about:

We are attempting to survive our time so we may live into yours.

Before I get to what’s important about that line for you, can we take a moment to appreciate the poetics? There’s so much meaning nestled into those folds of ambiguity: Einsteinian relativity, the interchangeability of space and time; metempsychosis, the transmigration of souls; mortality, loneliness, longing, hope; within humanity, the uncanny two-way permeability between individual and species; straightforward Cold War anxiety.

All of that packed into just thirteen words. Christ. The mind reels.

We are attempting to survive our time so we may live into yours.

As for the line’s specific relevance: when you think about it, it’s all we’re doing here in book publishing, isn’t it? Attempting to survive our time so we may live into others’? I’m going to go ahead and guess that’s the only thing that really matters to any of us: that survival, that recognition, that meaning something.

We may tell ourselves we want to make money as well, but come on: if that were really what we cared about, we’d all be investment bankers. A deeper gravity pulled us to this place, and we all know it.

We write and tinker and publish in order to find other people in the dark. We write because we’re terrified of our own invisibility. We write because we’re even more scared of meaning nothing to anyone than we are of dying. If our lives mean something—even if that meaning comes billions of years after we’re gone—then the prospect of going somehow becomes less painful.

Without such hope, how does one even live? (Spoiler alert: fascistically. Or not at all.)

We are attempting to survive our time so we may live into yours. This was what humanity was doing in the late 1970s, trying not to hijack or bomb each other into extinction; it’s also what President Carter and his speechwriters were doing when they wrote the Voyager letter. The line is metaphorical, about billions of people; it’s also literal, a first-person plural utterance from just a few guys. Viz.: Carter is dead now, but as you read his letter, his time lives into yours.

The act of writing is ever thus: a reach beyond the limits of one’s own spacetime, searching for a stranger’s hand in the dark. What a vulnerable, cuckoo, romantic thing to do.

We are attempting to survive our time so we may live into yours. What a succinct expression of the stakes involved in writing for the public. What a wonderful reminder to have compassion for ourselves and our colleagues.

What we are doing is no less than an attempt to survive against impossible odds. No wonder every rejection letter, unanswered email, or harsh review feels so existentially significant. No wonder every little development in the life of our books feels so high-stakes: it kind of is.

Writing is a courageous act, but like many courageous acts, it is also childlike and deranged. See also: mortifying. Literally mortifying. It is an attempt to survive our own finite time, despite the fact that we’re clearly going to die.

We are attempting to survive our time so we may live into yours.

It’s hopeless, really. We all know it. It’s hopeless for us; it’s also hopeless for the Voyager probes.

Both of the Voyagers are now well into interstellar space, caroming farther and farther into the black every second.1 Neither one will come even remotely close to another star for another 40,000 years, though, at which point Voyager 2 will pass a star called Ross 248 at a distance of approximately 1.7 light years.

In the astronomically unlikely chance there happens to be intelligent life orbiting Ross 248, here’s hoping they can spot a small spacecraft that far away and catch it faster than the speed of light. Otherwise: womp womp. Maybe next star.

Needless to say, chances are overwhelming that no extraterrestrial life will ever find the golden records. No one out there will ever try to decode President Carter’s beautiful letter or listen to the hours upon hours of music, the greetings in 55 languages.

No one will listen to Ann Druyan’s brainwaves, which are also on there. The program’s creative director recorded them while thinking about Carl Sagan, the colleague with whom she had just fallen overwhelmingly and rather problematically in love. Out in interstellar space, Ann’s love is still gold-plated, spinning all by itself; here on Earth, Carl hasn’t been around to love her back for a long, long time.

What chance in Hell did our records ever have, anyway? Don’t get me wrong: the Voyagers have held up remarkably, still transmitting data home after 47 years, despite the fact that their poor old pea brains contain just under 70KB of 1970s computational memory. (That’s not a typo.)

Even so, they’re going to be bricks soon. NASA has long estimated that 2025 will be the last year they’re able to transmit meaningful science back home to America.

The metaphor is almost too painful to point out.

We are attempting to survive our time so we may live into yours.

And yet. And yet. Even so bricked, the Voyagers will continue transmitting hope back home. They’re out there. Our writing and art are out there with them. It’s certainly not impossible that one day, someone will catch those things—us—and hold on, and at long last, we will mean something to someone, just as the possibility of them means something to us. The knowledge of that is everything; it is hope, it is endurance, it is survival of the self and the species. It is EVERYTHING. And it’s not subject to the limits of spacetime at all—to the agony of separation, the death of one man or machine.

Don’t ever let anyone—including you—tell you what you’re doing is stupid or pointless, ever again. Don’t you dare—even if, to borrow liberally from something Frederick Douglass once wrote to Harriet Tubman, the midnight sky and silent stars have thus far been the sole witnesses of your devotion.2 You’re doing the most important thing there is.

Happy new year. Keep going. Keep writing. Your people are out there, even in the dark.

13-17km per second. PER SECOND! After 47.5 years!

“The midnight sky and the silent stars have been the witnesses of your devotion” is what Douglass actually wrote; thanks to Gillian Brockell for making me aware of it.

I think this is the loveliest thing written about literature and the human condition that I have ever read, and it was written by my agent.

I come for the advice but stay for the metaphysics, I guess. What a resonant piece, and not only because I’m watching videos of LA burning while listening to Beautyland.